On a Pedestal

How do the arts help us answer the question,

“What is an appropriate monument for this time and place?”

by Caitlin Dwyer

Credit: Robert Reynolds The statue York: Terra Incognita stands along the path between Frank Manor House and Watzek Library, under some maple trees. Bronze feet rest on a mossy stone, not a large plinth. The name placard is small and affixed to a rock some distance away.

Associate Professor of Art Jess Perlitz asks her students what they notice. At the start of a course she teaches on monuments and memorials, the students cluster around famed sculptor Alison Saar’s depiction of York, a Black man who accompanied the Lewis and Clark Expedition and was enslaved by William Clark. They ask questions.

Why is York located on the side of the path? What is different about this sculpture from typical monuments or memorials? What is the significance of the map “scarred” into his back? Why is he smaller than life-sized?

“How do you render power?” asks Perlitz. For art students, the statue of York becomes a focal point for larger conversations about monuments and memorials, the Corps of Discovery and legacies of settler colonialism in Oregon. Inevitably, students begin to wonder about the context of this statue: the beautiful winding pathways, the library, the college named after two 19th-century historical figures.

Credit: Robert Reynolds

Perlitz starts her classes here to stimulate dialogue. Getting people talking is the same goal she had as co-organizer of Portland’s Monuments and Memorials Project (PMMP), a yearlong project that ended in spring 2022, which curated lectures, panels, and a culminating exhibit, Prototypes. Although focused on Portland, PMMP sought to engage with a larger conversation around public art.

PMMP emerged from Converge 45, a nonprofit organization that provides a curatorial platform for the visual arts in Portland and the surrounding region. Perlitz worked with Converge 45’s director, artist Mack McFarland, to spearhead the PMMP project. The goal: to bring a national conversation about monuments to the local level, asking Oregonians to participate in their own revisioning.

The nation is reckoning with its history, and thus with its monuments. Confederate monuments have come down in the South. In Portland, some podiums stand empty. Everywhere, cities are asking: Whose faces and names should adorn our squares? Which historical narratives should give way to new interpretations? Whose stories get told in stone?

Monuments and memorials can be catalysts around which we gather to talk about history, about community, about identity, about transformation. Because they are cast permanently, they provide physical embodiments of cultural narratives, about ourselves and each other.

In a time of vitriolic debate, Perlitz and McFarland imagined the arts as catalysts of conversation. Prototypes would be a thought experiment, intended to generate conversation and stimulate the imagination around what art can be in our public spaces.

“We decided we wanted to center the arts as a way of thinking through these problems,” says Perlitz.

PMMP came at a moment when Portland was reexamining its public spaces. Months of protest had dominated the 2020 news cycle, and protesters had pulled down statues around the city, from George Washington to Oregonian editor Harvey Scott. Sometimes the plinths stayed empty. Sometimes new statues went up in their place.

The movement to reexamine monuments is about seeing history clearly and consciously, says Reiko Hillyer, associate professor of history and director of ethnic studies. She explains that most of us go about our days ignoring the historical markers in our built environment.

“We just sort of walk by them,” Hillyer says. “One of the ways in which historical narratives become codified as common sense is by making a landscape that seems so intractable and seems so natural and kind of mundane in everyday life that you cease to question the power that made it, and the powers that are upheld by its making.”

PMMP wanted to ask those questions. It wasn’t designed to replace the old statues immediately with new ones. Instead, the organizers hoped Oregonians would begin to think beyond addition and subtraction to a more holistic view of what our public spaces could be.

An open call went out for submissions to the Prototypes exhibition in 2021. Rather than finished sculptures, artists submitted proposals for new public artworks.

For Perlitz, the imaginative nature of the exhibit was key, as it allowed for greater community participation. Not every submission came from an established artist; some came from groups with deep roots in the region.

Deciding which sculptures get built isn’t the point, Perlitz says. The exhibit offered a space for ideas. It was about the “messiness” of the process of talking with each other, honestly, about history, and about how we might go about making new monuments and memorials.

As a professor at Lewis & Clark, Perlitz is used to an academic environment that encourages conversation around tough topics. That liberal arts ethos, she believed, had to be brought into the public sphere. It was time for Portland to have some difficult conversations.

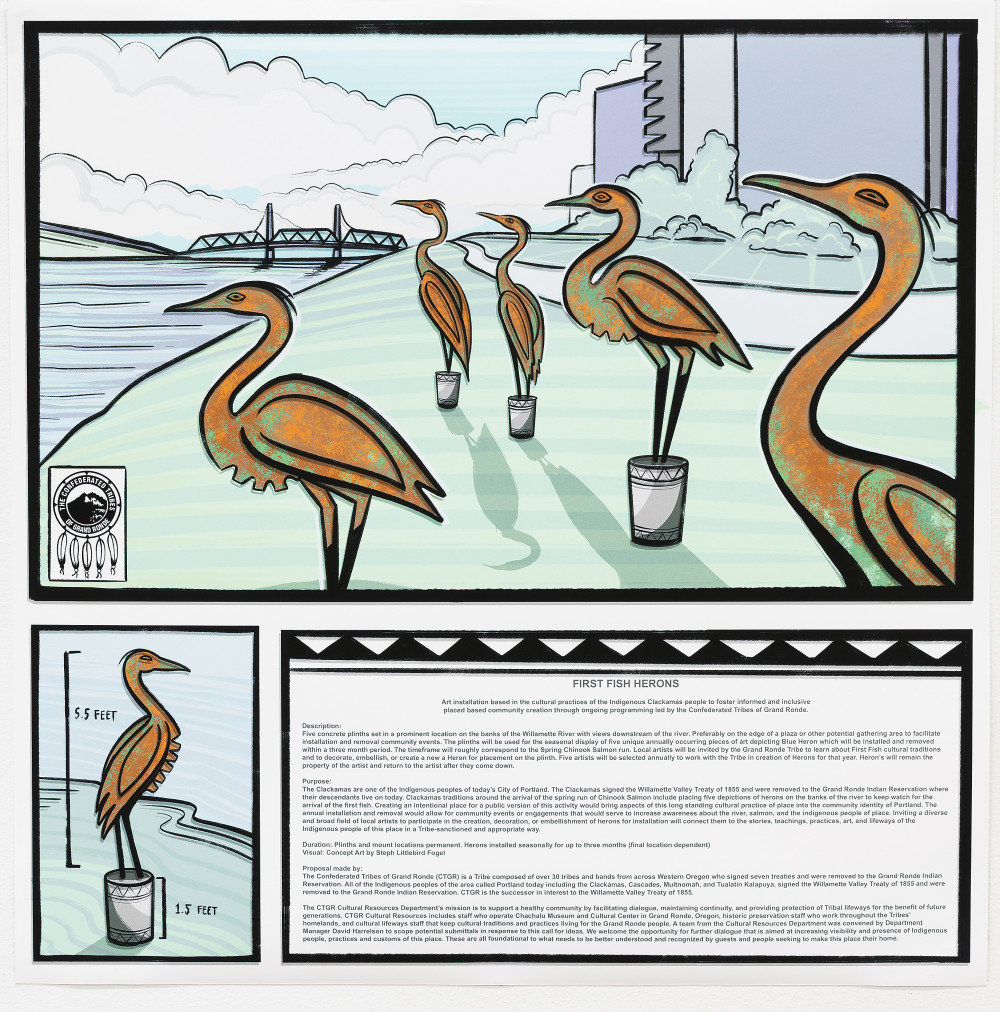

David Harrelson (Kalapuya) BA ’07 knew that the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde had to submit to Prototypes. As the cultural resources department manager for the tribes, part of his job has been to imagine ways to bring the art of the Columbia River basin to greater recognition through exhibits and public installations.

“Art is one of the most effective tools we have to demonstrate that we are the Indigenous peoples of this place, and we are still here,” Harrelson says.

Prototypes was just the kind of opportunity tribal members had been looking for: a chance to spur conversation around the ecosystems and original inhabitants of the region. Harrelson convened a working group and talked through possibilities. A small committee drafted ideas and sketches. The collaborative process was purposeful, reflecting tribal values, but also interrupting the usual narrative of how monuments are built.

Credit: Mario Gallucci

Monuments are often paid for by individual wealthy donors with a specific interest. According to Reiko Hillyer, they uphold particular narratives, but even more so, they uphold the worldview and authority of the donors and the makers.

“The Confederate monuments that went up in the 1890s said a lot more about the 1890s than they said about the actual mission and ideologies of the people in the Confederacy,” she says. “They are monuments to their makers, maybe their money, more than to their subjects.”

In that light, First Fish Herons, the tribes’ Prototypes submission, is particularly subversive. The monument is imagined as a rotating installation; on top of three stone plinths will sit carved herons, watching the river for fish. The herons will appear seasonally when fish run in the river, representing traditional fishing practices among the Clackamas people. Different artists will be commissioned to create the herons, so that no individual dominates. The temporal and collaborative aspects mean that tribal members will come to town regularly to install and uninstall the birds. At times, the monument may look unfinished, even empty, when the birds are absent. That absence, too, can be a focal point for reflection.

“There’s some real need to draw attention to the fishery that may not exist in our lifetime,” says Harrelson. Overall, the piece is about “creating definable moments in time when people can connect and look forward,” he says, as well as providing a sense of ritual.

Although Prototypes was ostensibly an exhibition of monuments, not every submission envisioned sculpture. Some played with or even poked fun at the idea of public art, trying to prod at our inherited ideas of what constitutes a monument.

Misha Davydov BA ’21 submitted a zine called Lenin Alive, which juxtaposed images of Vladimir Lenin with pineapple upside-down cake, rocket ships, and cucumber spa treatments. Davydov wanted to explore how Lenin’s physical body appeared in public space in Russia.

“I was interested in taking different representations of him and his monuments and putting those in contexts in which they normally wouldn’t appear,” says Davydov, who also helped install the exhibit.

Credit: Mario Gallucci

Davydov, a native Russian, experienced the images differently than an American viewer might. The disconnect interested them. They were curious to see “if anyone would see a reflection of their own context and environment and try to culturally ‘translate’ the images or see what parallels there are in American history.” The result is playful, irreverent, and thought-provoking.

Davydov’s zine will never become a traditional monument. Instead, it provokes the viewer to consider preconceived notions of who and what gets revered in stone, and how a monument’s meaning changes as time passes and its context changes. That urge toward provocation is one that Davydov developed during their time with the art department at Lewis & Clark.

The college experience “shaped not only how I make art, but how I think about things in a lot of ways … how I inquire into things or how I challenge things,” says Davydov. “It was incredibly formative.”

Much of the work of reimagining public space takes place intellectually. We can stand around a piece of art, examine it, critique it, disagree about it. The transformation takes place internally and in community, as we share and debate our narratives of ourselves. Art becomes a focal point, a way of fostering dialogue around difficult subjects.

For the Lewis & Clark community, this raises questions about a topic closer to home: the very name of the institution. What does it mean to be named for two historical figures whose trek forever changed the course of Indigenous history?

It’s not a comfortable conversation, says Perlitz, but it’s an important one. That kind of dialogue “holds the ideals of what a liberal arts college is,” she says. “We embrace that discourse because that is what we believe we are doing on this campus: building upon and reckoning with the knowledge we are handed.”

Changes to public space, whether they are monuments or names, need to go beyond inclusivity and become transformative, Reiko Hillyer asserts. Any conversation around Lewis & Clark’s name should include “deliberate institutional effort to be more collaborative with tribal organizations … and also incorporate Indigenous knowledge and study of Indigeneity into its curriculum,” says Hillyer. She cites the example of Georgetown University, which has established an archive that researches its institutional history around slavery and seeks to create scholarships for the descendants of enslaved people. That kind of work, she says, is an example of how academic institutions are beginning to grapple with history in difficult, productive way.

In Milwaukie Bay, where David Harrelson once rowed crew as an L&C undergraduate, First Fish Herons is coming to roost. The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde are in talks with the city and parks department to make the monument a reality.

“I think people are choosing a liberal arts education, in part, because they are interested in that murky territory and that discourse,” says Perlitz. In a liberal arts model, through art, students and community members can explore contradictions and come up with new ideas for honoring, mourning, and celebrating together.

Imagine a seasonal ritual where artists come to bring the herons to their stone bases. Imagine a public space that asks us to pay attention not just to individual historical figures, but to the cycles of a river that runs through our cities. Imagine kids playing under the herons, wondering what the birds are waiting for.

Caitlin Dwyer is a Portland-based writer.

L&C Magazine is located in McAfee on the Undergraduate Campus.

MSC: 19

email magazine@lclark.edu

voice 503-768-7970

fax 503-768-7969

The L&C Magazine staff welcomes letters and emails from readers about topics covered in the magazine. Correspondence must include your name and location and may be edited.

L&C Magazine

Lewis & Clark

615 S. Palatine Hill Road

Portland OR 97219

More Stories

Shifting Gears

After a remarkable 51-year career in politics, Rep. Earl Blumenauer BA ’70, JD ’76 prepares to retire, leaving behind a sprawling legacy reflecting his commitment to livable communities, transportation, the environment, cannabis legalization, animal rights, health care, and more.

Data Processors

In a cross-school collaboration, Professors Greta Binford and Liza Finkel prepare middle and high school teachers to weave real-world data science into their environmental curricula.

Advantage: Lewis & Clark

The first phase of Lewis & Clark’s strategic planning effort sets the stage for institutional distinction. The new process is iterative and dynamic— responsive to a world that won’t stand still.

Musical Note: Good vibrations

What’s better than hearing music? Feeling it!